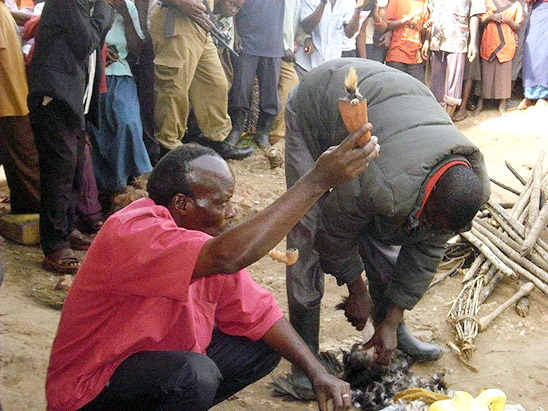

The healer reveals a witchcraft item “found” in the accused man’s house to the crowd. It probably came from the pockets of his assistant’s padded jacket.

About this week’s eSkeptic

In the small Ugandan village near the capital city of Kampala, a man named Ronald Kapungu had been accused of practicing witchcraft or hiring witch doctors to curse a nearby family. In this week’s eSkeptic, freelance reporter and travel writer, Justin Chapman, describes his experience at the witchcraft ceremony that he witnessed while covering the story with local journalist Luke Kagiri.

Justin Chapman is an author, poet, actor, and journalist. At age 19 he was elected to the Altadena Town Council and chaired its Education Committee. He has written for numerous publications, including the Pasadena Weekly, L.A. Weekly, Patch.com, and Berkeley Political Review. He received his degree in Media Studies from University of California, Berkeley.

All photos by Justin Chapman. Used with permission.

Witch Doctors and Con Artists

A First-Hand Account of Witchcraft in Africa

BY JUSTIN CHAPMAN, SKEPTIC MAGAZINE, 4/17/2013

I’m a freelance reporter and travel writer. Over the course of three months in 2012 I traveled by myself by buses and trains from Cape Town, South Africa to Mityana, Uganda. One of the things that struck me was the apparent contradiction of the practice of witchcraft, especially in East Africa. As I reached Zambia I started to hear about the history of witchcraft. I was surprised to find out in Uganda that the practice is still very much alive, even among otherwise intelligent people.

The Ugandan constitution allows all kinds of worship, but has a (very weak) provision from 1957 called the “Witchcraft Act” setting forth punishments for those who practice it. However, a court later voided the sections about witchcraft for having vague definitions. You are not allowed to threaten someone with witchcraft, but proving that someone has practiced it, let alone succeeded in utilizing evil spirits, is impossible at best.

Unfortunately, the villagers are wary of modern hospitals and doctors, and once they are convinced witchcraft is being practiced, the sick will not visit a hospital because they think the doctors will not be able to find, let alone cure, the problem. This really is a tragedy because if someone has malaria, for instance, obviously the hospital is the place to go. But if they believe witchcraft is the source, they won’t go, leaving themselves open to sickness and death.

While in Uganda I traveled around with a local journalist named Luke Kagiri and helped him cover his various assignments. One day we rode on a boda-boda (motorcycle taxi) about halfway between Mityana and the capital city of Kampala, about an hour’s ride, for a witchcraft ceremony. The driver turned off the highway onto a walking path that led us deep into the bush to the village where a man named Ronald Kapungu had been accused of practicing witchcraft or hiring witch doctors to curse a nearby family. As proof of Ronald’s wrongdoing, the afflicted family claimed that a male relative had died, the husband was supposedly acting crazy like he was possessed, and the wife was ill.

Several villagers had attacked Ronald’s house the week before and he fled the village, hundreds of miles away. Riot police had to come and shoot tear gas into the crowd to disperse them. So the villagers called a “traditional healer” to come and use his “powers” to confirm or deny whether Ronald had in fact been practicing witchcraft.

When Luke and I arrived, there were about 200 people from the surrounding small villages to witness the ceremony. I was the only mzungu (white person) there. Of course everyone was staring at me, but they knew I was with Luke and that we were filming the ceremony for Bukedde TV, the local news station. This gave us access that the crowd didn’t have.

Under the Ugandan constitution, large gatherings of people are not allowed without permission from the police and without police presence. Indeed, there were several uniformed officers, who stood in front of the crowd (which was compacted together on a small hill 20 feet from Ronald’s battered house, people watching among the trees, cows, pigs, and chickens in the bush) while riot police, automatic rifles at the ready, stood at various points in a circle about 40 feet from and around the crowd.

The traditional healer, a well-dressed man in his late 50s wearing an expensive watch (not what you would picture a witchcraft healer would look like or be wearing), had to get clearance from the local police as well as the chiefs of the village before he arrived.

The healer took his time, walking around the square house, tapping at various things with his black walking stick that curved near the top like a handle and continued up another foot (supposedly the source of his “powers”), and finally entering the house to look around. He didn’t bring a bag, but two men came with him and one of them had a thick black rain jacket on with many pockets. The healer exited the house and the three of them took a canister filled with local brew and walked around the perimeter of the house, splashing the alcohol against the outside walls of the house. They did the same thing with a canister of milk, then one of the guys tossed small stones up to hit the tin awning that stretched out beyond the roof.

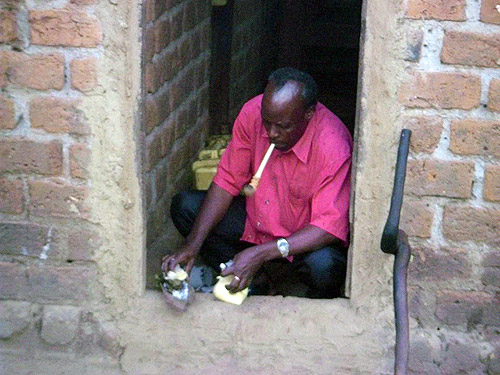

A “traditional healer” performs a ceremony in the doorway of the house of an accused witch. The walking stick outside the door is the source of his power.

The healer then placed a bag of flour and a wooden bowl filled with an unknown substance at the foot of the door. He lit his pipe, smoked slowly, answered his expensive cell phone and talked for a minute or so, looked around like he didn’t care, and used his stick to mix the substance in the bowl. After smoking for a few minutes, he went back into the house. Luke motioned for me to follow him. We walked into the house in time to see the healer’s associate, the one wearing the black rain coat, slip a curved, cone-shaped wooden handle with herbs sticking out of the top into a soft, weathered briefcase on the ground.

We went outside and the healer emerged with the bag, which he informed the crowd he suspected contained the witchcraft items.

After another few minutes he opened the bag and pulled out the wooden handle. He held it up to show the crowd (see photo at top of this article), which went wild with excitement, for this was supposed to be the witchcraft item used by Ronald to bewitch the family. I already knew the whole thing was baloney, of course, but when I saw what the healer did, I realized the scam. The man who was wearing the black raincoat had the cone-shaped handle hidden in his jacket pocket the entire time.

Their suspicions confirmed, the villagers began throwing large pieces of wood into a pile in front of the house to make a fire. They brought two chickens over and removed the feathers from their necks, then sliced the heads off right in front of me and threw them into the pile. A guy doused the wood with kerosene and lit the fire. The healer threw the bags in as well as the witchcraft item, which supposedly contained all the evil spirits. People grabbed whatever they could and threw the stuff into the fire. More gas was splashed on, and it became the tallest, hottest bonfire I’d ever seen. Everyone had to back away about 20 feet because it was so hot.

As about 200 people watch, gasoline is poured on a bonfire and the alleged witchcraft items are burned to destroy the evil spirits.

Then the already elated, besotted crowd marched behind the healer down a path to the victim family’s home, about 100 yards down the hill. Luke and I ran in front to get pictures and film the single file hikers. When we got there, the healer approached the sick woman and rubbed the curve of his stick around her head, muttered a few words, and gently lifted his hands to the air, as if to say, “Evil spirits be gone.”

I followed the healer into the victim family’s home, which he inspected thoroughly but still with an uninterested attitude. I saw the room where the family members slept, on thin mats on a hard floor.

The crowd was angry. They wanted vengeance. Everyone marched back to Ronald’s house with the intention of destroying it. The police were there to stop them, and Luke told me, “If there is violence, stand behind the police, because they will shoot in front of them into the crowd, not behind.” So we stayed behind the police who stood between the crowd and the house. Ronald’s father, a very old, frail man on crutches, claimed that his son was innocent. The police told the crowd to disperse. The crowd timidly backed off, but would surely be back later to demolish the house.

The police told Luke and me that they were leaving and that we should leave as well, because if something happened they would not be able to protect us. I wanted to see some mob violence, but it’s probably better that we got back on the boda-boda and booked it out of there, following the healer who also rode on a boda-boda. I didn’t think we were in danger but Luke told me that the crowd knew they could be identified on television and so when the police left they could potentially attack us.

The villagers will go looking for Ronald, and if they find him or if he ever returns to the village, he will be killed. Many people die this way. Even if Ronald was practicing witchcraft or had hired a witch doctor to put a curse on the family, so what? This stuff isn’t real. The only thing he is allegedly guilty of is sending bad vibes. The accused are the victims, not the “bewitched.” People practice witchcraft in Africa for various reasons, but usually because they are jealous of someone for having more money, allegedly having an affair, having beautiful children…anything. And people are killed and their homes destroyed because of it.

Meanwhile, the traditional healer is paid between 500,000 and 1,000,000 Ugandan shillings (about $200–$400 U.S.) for his “services,” which is a lot of money for villagers to cough up. He’s ripping them off, and he also adds to the confusion by spreading rumors about certain people practicing witchcraft.

According to the Ugandan constitution, in order for the police or a traditional healer or anyone to search your home, they must have a search warrant, like in America. At this ceremony, they had no search warrant and yet the healer and others were allowed to enter Ronald’s home, search it, seize items from it, burn them, probably destroy the house, and later most likely murder him. If Ronald knew the law, which he doesn’t, he could sue the police, the healer, and others. He could say his name and image were tarnished and be compensated 2,000,000 shillings for that as well as for the destruction of his home and property, such as the bags. The chances that he would win the case are extremely high, because how can anyone prove in court that evil spirits were the cause of the victim family’s illnesses and death? I told Luke I wanted to help Ronald, to give him the pictures and footage we took of the ceremony so he could use them in court to prove he was not served with a search warrant.

“Ronald could only use the footage and pictures if we published them in the newspaper or broadcast them on TV,” Luke told me. “If we supply him with the raw clips and photos, the villagers would think we were spies trying to help him the whole time, instead of attending the ceremony to write and shoot a legitimate journalism story about it.”

We would be outcasts in the community, and since Luke lived there and people knew who he was, he couldn’t do that for Ronald. The fact remains that if these people really want to hold onto this outdated belief system, fine. But why not try a healer and a real doctor in a real hospital? What have they got to lose? They just think it’s a waste of time, because the real reason for unexplainable things is invisible spirits and powers that can’t be proved. The fact that Ugandans are mostly Christian doesn’t dissuade uneducated segments of the population from letting go of their superstitious beliefs regarding witchcraft.

How interesting. How bizarre. ![]()