Read the July 2022 issue of Justin Chapman's Newsletter, featuring the new episode of "NewsRap Local," the 3rd part of his series on Jack Parsons, his Pasadena Star-News article about Jerry Stahl's new book, some recommendations for good reads, news to keep an eye on, and more!

Award-Winning Journalist & Pasadena's District 6 City Councilmember's Field Representative

Justin Chapman writes, produces, and hosts a monthly TV news talk show on Pasadena Media's TV channel, called "NewsRap Local with Justin Chapman." The sixteenth episode aired Friday, July 22, 2022. The guest was Pasadena City Council member Jess Rivas. Watch the full episode below:

Jerry Stahl’s life, in many ways, was collapsing under the weight of personal despair:

Divorce. Depression. An all-but-dead television pilot.

But this was 2016. One of the most negative, toxic and consequential presidential elections in memory was underway – and Stahl, following along, also despaired for the future of the world.

So Stahl, an author and screenwriter, did something curious: He visited the epicenters of human despair. Stahl, who is Jewish, took a bus tour of World War II concentration camps in Germany and Poland as a way to gain perspective on his sorrow and the world’s tumult.

And then he turned it into a book.

“Nein, Nein, Nein! One Man’s Tale of Depression, Psychic Torment, and a Bus Tour of the Holocaust,” was released Tuesday, July 5, by Akashic Books.

As a memoir, the book is deeply personal, discussing Stahl’s efforts to work through his depression, professional troubles and other issues.

But “Nein” also draws a connection between the Nazis of history, and the rise of authoritarianism, anti-Semitism and racism around the world, which multiple studies, polls and news reports have detailed.

The dueling narratives that would ultimately comprise “Nein,” along with the horrors of the Holocaust, converged on Stahl’s bus tour through Auschwitz, Dachau and Buchenwald.

Stahl, 68, is the celebrated writer of 10 books and several television shows and movies.

Decidedly not a bus tour kind of guy, he decided to visit concentration camps to learn more about World War II and the Holocaust, and get some perspective on the personal and professional issues he was dealing with at home in Southern California.

The trip was meant to focus his out-of-control sadness, regret and fear, Stahl said.

“I am trying to discover (for) myself what I was feeling, because in this particular case the subject matter is so deep and dark that you’re operating on two levels,” Stahl said. “You’re writing about the crime of the 20th century, but you’re also writing about your reaction to it.”

While Stahl – who has lived throughout the Southland, including in Pasadena and San Marino – is a successful Hollywood writer, his life has been marked by its own, narrower type of regret and tragedy.

Stahl, who grew up in Pittsburgh, moved west after his father, a federal judge who served as Pennsylvania attorney general, died by suicide.

After winning a Pushcart Prize, a well-regarded literary award, in 1976, Stahl wrote for magazines and newspapers in the 1970s and 1980s. His first paying gig was for the Santa Cruz Free Press when he was 20, for which he made $8 an article.

In the ’80s and ’90s, Stahl wrote for popular and cult television shows, such as “ALF” and “Twin Peaks” – yet he did so while maintaining a vigorous heroin addiction. (He’s been clean for more than 25 years.)

Stahl is also the author of several transgressive novels, including “Happy Mutant Baby Pills,” “Bad Sex on Speed, Pain Killers” and “I, Fatty,” a fictionalized autobiography of silent film comedian Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle that was optioned by Johnny Depp.

But “Nein,” which Robert Downey Jr. recently optioned, is most similar to the book for which Stahl is best known, his 1995 heroin memoir, “Permanent Midnight.”

“Permanent Midnight” became a movie starring Stahl’s friend Ben Stiller in 1998.

Underscoring the similarities between the two memoirs, the 92nd Street Y in New York hosted a book launch for “Nein” in mid-June – featuring a conversation between Stahl and Stiller.

Stiller hung out with Stahl for nine months while the studio tried to finance the movie.

“Having Jerry there was invaluable to me, because he gave me the confidence to be this guy who was going through experiences I had never gone through,” Stiller told this reporter. “He supported me in it fully and it really made the difference.”

“Nein,” like “Permanent Midnight,” is written in a highly personal, hold-nothing-back style. Stahl said he wouldn’t quite call it “therapeutic” to put every sordid detail on public display – but certainly a form of expiation.

The bus tour, Stahl wrote in “Nein,” was “engendered in despair and (aspirationally) a cure for it at the same time.”

The show he was writing at the time was about a fun, happy-go-lucky marriage between an older guy and a younger woman who were having a baby. It was based on his 2015 memoir “OG Dad” – about the marriage that was falling apart as he worked on the pilot.

“You’re walking this tightrope, because you think you’re gonna go in and have this tremendous revelatory experience, which you do on one level,” Stahl said. “On the other hand, the first thing you see at Auschwitz is a snack bar with people eating pizza and drinking Fanta, so there’s a bit of a disconnect.”

That snack bar is where prisoners were once tattooed and got their heads shaved.

“The actual pizza ovens are, on some level, just as disturbing as the ovens in the crematorium,” Stahl wrote in “Nein.” Especially when you consider “the average prisoner’s nutritional intake came to roughly 800 (barely edible) calories a day.”

The subject matter sounds like a downer. But Stahl, who’s known for his dry-but-witty style, manages to write about that scene – and others – in a humor-steeped, yet meaningful, way.

Some of the most memorable scenes in the book, in fact, are infused with gallows humor:

There’s the story of Stahl visiting the gift shop at Dachau.

There’s the time he ran into a sliding glass door at the Buchenwald cafeteria.

And there’s the dichotomy of Stahl standing in a place of cruelty and death while his tour guide hopes aloud that the crowd wore comfortable shoes for the Auschwitz visit.

“We’ve got a lot of walking,” the tour guide said, according to “Nein.” “And we’re behind schedule.”

But the trip wasn’t all humorous incongruities.

Visiting and writing about Holocaust sites did reveal a certain truth.

“None of your problems—and by ‘your’ I mean ‘mine’—none of it matters,” he said. “This is so huge and so much bigger than my personal torments and idiocies and struggles.

“And I always wonder about the prisoners themselves,” Stahl added. “How far into their captivity did all the obsession over success, money, marriage, sex, ambition, how far did that last before it just dissipated into the straight-up struggle for survival?”

Yet, his personal and professional struggles weren’t the only contributors to Stahl’s emotional despair during that trip.

He also feared for the world around him – that the horrors of the Holocaust would turn into a type of prologue for society’s future.

Stahl’s fears, as it turns out, weren’t entirely unfounded.

The year 2020, for example, was the 15th in a row during which global freedom declined, according to a country-by-country report published by the nonpartisan Freedom House.

That organization – which researches the state of, and advocates to increase, freedom around the world – found that in 2020, the share of countries designated “not free” had reached its highest level since 2006.

The United States saw its freedom score also decline, according to that report.

Russian President Vladimir Putin, meanwhile, is currently conducting a war in Ukraine – six years after the authoritarian was accused of meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

At home, anti-Semitism is on the rise in the United States, according to the American Jewish Committee. The number of hate crimes in California spiked in 2021, the state’s Department of Justice said in a report published late last month.

And Stahl’s conclusion, for many people, won’t be particularly comforting.

“The Holocaust of the 1940s is done,” Stahl writes in “Nein,” but “the ongoing genocide-adjacent assault on human rights—globally, locally, nationally—continues.”

Stahl’s final message is either one of hope or tragic fatalism, depending on your perspective.

But Stahl is a man who has experienced depression and addiction, flitted between professional success and failure – and yet he has never lost his gallows humor.

Perhaps that makes it easier to understand why Stahl says his message to readers is one of hope.

“My message of hope is that the Holocaust was not an exception,” he wrote in “Nein.” “It is the time between holocausts that is the exception.

“So savor these moments,” Stahl added. “Be grateful. Even if the ax is always falling.”

Jerry Stahl will discuss, read and sign “Nein, Nein, Nein! One Man’s Tale of Depression, Psychic Torment, and a Bus Tour of the Holocaust” during a conversation with Evan Wright at 7 p.m. July 28 at Book Soup, 8818 Sunset Blvd., in West Hollywood. For more information, visit booksoup.com.

ORIGINAL ARTICLE:

Jerry Stahl Learns to ‘Savor the Moments Between Holocausts’ in His New Book

Nein, Nein, Nein! One Man’s Tale of Depression, Psychic Torment, and a Bus Tour of the Holocaust, about LA author Jerry Stahl’s bus tour of European concentration camps, makes the connection to the current political environment and delivers a reflective tome infused with gallows humor

By Justin Chapman

When author and screenwriter Jerry Stahl embarked on Holocaust tourism—bus touring the World War II concentration camps of Germany and Poland—in the heat of the 2016 U.S. presidential election for his latest book, he felt like he was “visiting the future.”

In Nein, Nein, Nein! One Man’s Tale of Depression, Psychic Torment, and a Bus Tour of the Holocaust, out Tuesday, July 5, by Akashic Books, Stahl draws a clear connection between the Nazis of history and the rising alt-right and authoritarianism of today.

“You have to remember that Hitler was considered an ass clown, too, initially,” Stahl said. “He was the subject of great mockery and derision and nobody took him seriously. The same could have been said for Trump. He was a sideshow, but then the joke turns out to be on us when that sideshow becomes the center ring and the main event—and it turns out we’re the sideshow.”

Referring to outgoing Rep. Madison Cawthorne (R-North Carolina), who posted a photo of himself on Instagram in 2017 at the Eagle’s Nest in Berchtesgaden, Germany—along with a caption that said Adolf Hitler’s vacation home had “been on my bucket list for awhile”—Stahl said that “in America now, that’s almost mainstream. Obviously, Joseph Goebbels invented the Big Lie, but needless to say, it still works.”

Stahl, 68, is the celebrated writer of 10 books and several TV shows and movies. He began his career writing for magazines and newspapers in the 1970s and 80s after winning a Pushcart Prize in 1976. He grew up in Pittsburgh and moved west after his father, a federal judge who served as attorney general of Pennsylvania, committed suicide. Stahl’s first paying gig was writing for the Santa Cruz Free Press when he was 20, for $8 an article. In the 80s and 90s, Stahl wrote for TV shows such as “ALF” and “Twin Peaks” while maintaining a vigorous heroin addiction. Today, he’s been clean for more than a quarter century.

His transgressive novels include, among others, Happy Mutant Baby Pills, Bad Sex on Speed, Pain Killers and I, Fatty, a fictionalized autobiography of silent film comedian Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle that was optioned by Johnny Depp. Robert Downey Jr. recently optioned Nein.

But Nein is most similar to the book for which Stahl is best known, his 1995 heroin memoir, Permanent Midnight, which was made into a movie starring his friend Ben Stiller in 1998. On June 12, the 92nd Street Y in New York hosted a book launch featuring a conversation between Stahl and Stiller about Nein.

“Ben did a lot of research [for the movie version of ‘Permanent Midnight’],” Stahl said. “I took him down there on Eighth and Alvarado and Fourth and Bonnie Brae and all those old stations of the LA junkie cross. He lost a ton of weight, made himself really sick and made himself feel and look like shit. It was hardcore, man. It was very De Niro ‘Raging Bull’ and Christian Bale ‘The Machinist.’ He went way out there.”

Stiller, who hung out with Stahl for nine months while the studio was trying to get financing for the movie, told this reporter that “having Jerry there was invaluable to me, because he gave me the confidence to be this guy who was going through experiences I had never gone through. He supported me in it fully and it really made the difference.”

Since then, Stahl has written several episodes of “CSI,” “Maron,” “Escape at Dannemora,” the HBO movie “Hemingway & Gellhorn” and many others. He has recently lived in San Marino, Silver Lake, Pasadena and Mt. Washington.

Nein, like Permanent Midnight, is a memoir written in a highly personal, hold-nothing-back style. He wouldn’t quite call putting every sordid detail on public display “therapeutic,” but certainly a form of expiation.

“I am trying to discover myself what I was feeling, because in this particular case the subject matter is so deep and dark that you’re operating on two levels: you’re writing about the crime of the 20th century, but you’re also writing about your reaction to it,” he said. “And you’re walking this tightrope, because you think you’re gonna go in and have this tremendous revelatory experience, which you do on one level. On the other hand, the first thing you see at Auschwitz is a snack bar with people eating pizza and drinking Fanta, so there’s a bit of a disconnect.”

That snack bar is where prisoners used to get tattooed and their heads shaved. “The actual pizza ovens are, on some level, just as disturbing as the ovens in the crematorium,” he wrote. Especially when you consider that “the average prisoner’s nutritional intake came to roughly 800 (barely edible) calories a day.”

The subject matter sounds like a downer, but Stahl, who’s known for his bone dry but always witty sense of humor, manages to write about it in a hilarious yet meaningful way. Some of the most memorable scenes in the book are infused with gallows humor.

Such as his visit to the gift shop at Dachau. Or when he ran into a plate glass sliding door at the Buchenwald cafeteria. Or when he overheard a young man in khaki pants and collared shirt—à la Charlottesville—compare the crematoriums to pizza ovens and mansplain to his newlywed on their honeymoon that the gas chambers weren’t real while they stood in the Auschwitz showers where countless Jews were gassed with Zyklon B.

Or how about when someone on his tour bus whisper-sang, “One hundred bottles of Zyklon B on the wall, one hundred bottles of Zyklon B, take one down and spray it around, ninety-nine bottles of Zyklon B on the wall…” and he looked around to see if anyone else heard, or if it was for his benefit (Stahl is Jewish).

Or when his tour guide said, “I hope you are all in comfortable shoes for Auschwitz. We’ve got a lot of walking. And we’re behind schedule.” As Stahl writes, you wouldn’t want anyone to “succumb to death camp bunions. In the end it’s always a battle between personal comfort and psycho-historical horror. It feels vaguely wrong that the concentration camp experience doesn’t hurt. Then again, nobody’s marketing actual terror and atrocity, just the experience of strolling around where terrifying atrocities were committed.”

Nein originally appeared in a shorter form as a six-part series for Vice called “A Tour of Hell, from Hell,” but he always planned to turn it into a book, it just took him a few years to “find a way in.” The challenge was that by the time he sat down in 2020 to start that process, his notes from the trip were mistaken as trash and thrown out. So he wrote it from memory, though the book is full of specific details and conversations.

He was also dealing with a litany of personal and professional issues at the time of the trip—divorce, depression and bombing a TV show pilot gig in which he had to write about a fun, happy-go-lucky marriage between an older guy and a younger woman who were having a baby, based on his 2015 memoir OG Dad that the network executive never read, while said marriage was falling apart. As he wrote in the book, his trip was “engendered in despair and (aspirationally) a cure for it at the same time.”

But visiting and writing about Holocaust sites did reveal a certain truth to Stahl: “None of your problems—and by ‘your’ I mean ‘mine’—none of it matters,” he said. “This is so huge and so much bigger than my personal torments and idiocies and struggles. And I always wonder about the prisoners themselves. How far into their captivity did all the obsession over success, money, marriage, sex, ambition, how far did that last before it just dissipated into the straight up struggle for survival?”

Stahl concludes the book by pointing out that while “the Holocaust of the 1940s is done, the ongoing genocide-adjacent assault on human rights—globally, locally, nationally—continues. My message of hope is that the Holocaust was not an exception. It is the time between holocausts that is the exception. So savor these moments. Be grateful. Even if the ax is always falling.”

Stahl is always working on more novels and screenplays. You haven’t seen the last of his brutal, incisive take on this world yet.

Jerry Stahl will discuss, read and sign Nein, Nein, Nein! One Man’s Tale of Depression, Psychic Torment, and a Bus Tour of the Holocaust in person and in conversation with Jonathan Ames at 7 p.m. on July 5 at Stories Books & Café, 1716 W. Sunset Blvd., Los Angeles, and in conversation with Evan Wright at 7 p.m. on July 28 at Book Soup, 8818 Sunset Blvd., West Hollywood. For more information, visit storiesla.com and booksoup.com.

Exploring the Occult World of Jack Parsons

Seventy years ago, on June 17, 1952, Jack Parsons—rocketry pioneer, self-proclaimed Antichrist, disciple of Aleister Crowley and explosives expert, whose work helped lead to the founding of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL)—died in a mysterious, city-shaking explosion in his home lab in a converted coach house behind a mansion on Millionaire’s Row in Pasadena. Was it suicide? Murder? An accident? We still don’t know. What we do know is here, in this 3-part series. (For Part 1, published June 17, please click here. For Part 2, published June 25, click here.)

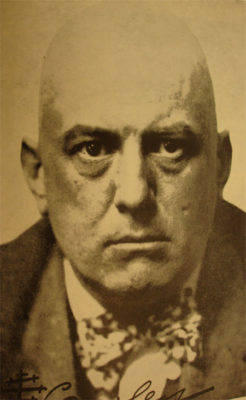

Aleister Crowley was a mountain climber, poet, chess player, writer and mystical magician. And he was one of the most controversial spiritual figures of the 20th century. He developed occult philosophies, practiced sex magic and called himself the Beast 666. The British tabloids called him “the wickedest man in the world.”

He was also the spiritual mentor of one Jack Parsons, the rocketry pioneer from Pasadena whose fuel inventions led to the founding of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

Crowley was born Edward Alexander Crowley on Oct. 12, 1875, into a strict, Biblical literalist family in Leamington Spa, England. He joined the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, an occult society in Victorian London. In Egypt, on a trip around the world, he and his wife Rose took mind-altering drugs such as ether, and she told him the god Horus wanted to talk to him. He subsequently dictated what became The Book of the Law, the founding text of his Church of Thelema, which he believed was communicated through him by a superhuman being.

A man named Theodor Reuss told Crowley that he was publishing the secrets of a group he helped found in Germany, the Ordo Templi Orientis (Order of the Temple of the East, or OTO), a quasi-Masonic group that practiced sexual magic. Crowley joined OTO in 1912 and soon controlled it. He started an abbey in Sicily where his followers put his teachings into practice. One young college student died from encentitis from mountain spring water, and his wife told the British tabloids fantastical stories about Crowley’s “cat blood drinking cult.” This cemented Crowley’s controversial reputation.

He spent the rest of his life in England managing sects of OTO around the world—including in Pasadena—and suffering from chronic bronchitis and heroin addiction until his death on Dec. 1, 1947, at age 72. In 1967, the Beatles’ album “Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” included his image on the cover, resulting in him becoming a cult hero for some.

But Parsons, who died in 1952 of an explosion in Pasadena (see part I of this series here), and whose rocketry work led to the founding of JPL (see part II here), had been a loyal disciple of Crowley as early as 1939.

Do what thou wilt

In January 1939, Parsons was first introduced to OTO and on Feb. 15, 1941, he and his first wife Helen were initiated into the Agape Lodge of the OTO. OTO had a tiered degree system, and Parsons would often jump ahead and perform rituals higher than his grade.

“The libertarian spirit of the OTO made it an accommodating home [for Parsons] in the days when homosexuality was illegal; an ethos of permissiveness was not merely a lifestyle at the OTO but a part of their religious practice,” Fraser MacDonald wrote in Escape from Earth: A Secret History of the Space Rocket. “Parsons, who oscillated between same-sex attraction and revulsion, found the scene intriguing.”

Parsons’ OTO motto was “Thelema Obtentum Procedero Amoris Nuptiae,” incorrect Latin for “the establishment of Thelema through the rituals of love.” George Pendle noted in Strange Angel: The Otherworldly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside Parsons that “transliterated into the Cabbala, the initials of his motto gave him the magical number of 210, with which Parsons would take to signing all his official OTO correspondence.” 210 would later become the number of the freeway that runs through Pasadena.

Members of OTO believed “sexual ecstasy could lift one to a different plane of consciousness,” Pendle wrote. “Perhaps the most well known of the OTO’s members in local circles was Roy Leffingwell, a pianist and composer who was also known as ‘Pasadena’s Greatest Booster’ from his role as the official announcer of the city’s annual Tournament of Roses.”

By following the OTO’s philosophy of “Do what thou wilt,” relationships soon started to fall apart. In June 1941, 27-year-old Parsons began an affair with Helen’s half-sister, 17-year-old Betty, who was living with them. Shortly after that, Helen began an affair with Wilfred Smith, head of the Agape, and they had a son. (Both Helen and Betty suffered sexual abuse from their father, Burton Northrup). Jack and Helen divorced.

“Shortly before her death in 1998, Betty told her daughter Alexis that [Parsons] initiated their sexual relationship when she was just 13—two years before the Parsons were involved in the OTO,” MacDonald wrote.

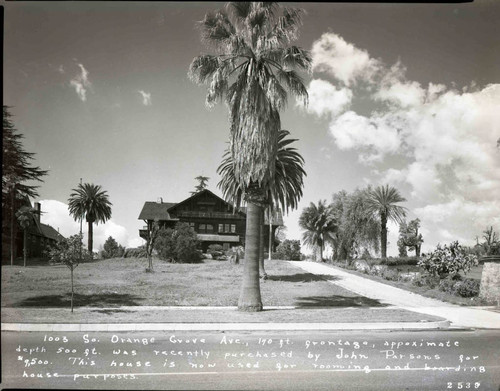

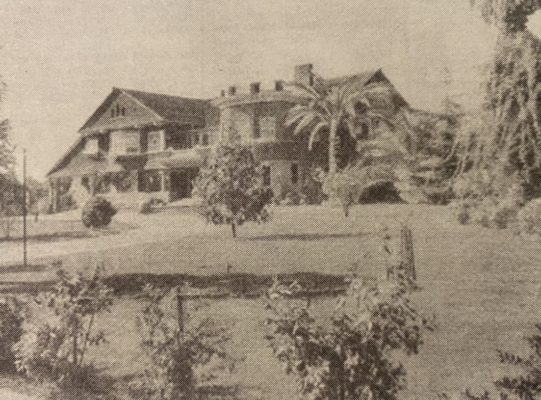

In 1942, Parsons moved to 1003 S. Orange Grove, a mansion next door to Lilly Anheuser Busch that became known as both the Parsonage and Grim Gables, and turned it into a Gnostic Mass temple where they hosted OTO gatherings—including orgies and magic rituals. The mansion was the former home of Arthur Fleming, Caltech benefactor and lumber millionaire who hosted Caltech luminaries such as Albert Einstein in that house, which he built in 1899 as one of the first Craftsman houses in Pasadena.

Parsons, Betty, Helen and Smith all lived in the 11-bedroom abode along with an eclectic and debaucherous group of people, many of whom regularly swapped partners sexually. Pendle called it a “Dionysian climate of excess.”

In 1942, Pasadena police received an anonymous letter that “black magic,” “sex perversion” and other “strange goings on” were taking place at the Parsonage, so the FBI went to the house to investigate, one of many times.

“They would never find anything incriminating,” Pendle wrote. “Nevertheless the FBI did open a file on Parsons, detailing his link to a ‘love cult.’ By the end of his life, the file would stretch to nearly 200 pages.”

Parsons told police Thelema was “dedicated to the freedom and liberty of the individual” and that they “were anti-communistic and anti-fascist,” according to Parsons’ FBI file. The agents found “nothing of a subversive nature” but noted that they had heard the house was “a gathering place of perverts.”

Babalon Working

By this point, Parsons was regularly drinking homemade absinthe, smoking cannabis and taking cocaine, amphetamines, morphine and peyote. Crowley soon banished Smith and Helen from the Parsonage and installed Parsons as head of the Agape.

Parsons put an ad in the paper for renters that said “only bohemians, artists, musicians, atheists, anarchists, or other exotic types need apply for rooms—any mundane soul would be ceremoniously ejected,” Alva Rogers, a fellow tenant, recounted in an essay titled “Darkhouse” in a 1962 issue of Lighthouse fanzine, published by the Fantasy Amateur Press Association. “This ad, needless to say, created quite a flap in Pasadena when it appeared.”

In 1942, Parsons met science fiction author, U.S. Navy officer and future Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard at the Mañana Literary Society, a gathering of science fiction writers. After the war, Hubbard moved into the Parsonage. Parsons fell under the man’s spell, enamored with his wild tales of adventure around the world as a member of the Explorers’ Club, during the war with American intelligence and aboard submarines, and other fantastical tales such as lassoing a polar bear on an ice floe near Alaska’s Aleutian Islands and being shot by aboriginal arrows.

Parsons taught Hubbard about Crowley’s Thelema philosophy and they fenced without masks in the main room of the house. But soon, Hubbard and Betty began a blatant affair. Parsons, who preached what could later be termed “free love” and disavowed jealousy, was jealous.

In 1944, Parsons had been pushed out of Aerojet, the company he co-founded to develop and sell Jet-Assisted Take-Off (JATO) rockets to the military, and he was no longer affiliated with JPL. The twin pressures of losing Betty and Aerojet seemed to cause him to have a breakdown.

He began practicing black magick, witchcraft and voodoo. From December 1945 to March 1946, he performed a series of intense magical rituals called Babalon Working in an effort to conjure up an “elemental mate” using his own blood and semen, in order to then birth a “moonchild.” He chanted in the Enochian tongue, developed by 16th century alchemist Dr. John Dee, and drew pentagrams in the air. He believed he experienced supernatural phenomena, but it was likely Hubbard pulling a fast one on him. However, his future second wife Marjorie Cameron soon appeared at the Parsonage.

“He immersed himself deeper and deeper in his magic with an excitement that bordered on mania,” Pendle wrote. “His letters and notes from the time reveal his exaggerated self-esteem, racing thoughts, persistent agitation, and, in the case of Hubbard’s visions, poor judgment—all could have been signs of some form of manic episode.”

‘Obvious victim prowling swindlers’

Parsons foolishly entered into a business partnership with Hubbard and Betty called Allied Enterprises in which they agreed to pool all of their resources for the benefit of all partners. He invested nearly $21,000 into Allied Enterprises, while Hubbard added less than $1,200. Betty contributed nothing.

Hubbard proposed that he and Betty travel to Miami and buy three yachts with the pooled funds, then sail the boats back to Los Angeles to sell them at a marked-up price. Somehow, Parsons agreed. They left with his money, and he soon couldn’t keep his new Vulcan Powder Corporation going.

A telegram from Crowley read, “Suspect Ron playing confidence trick. Jack Parsons weak fool. Obvious victim prowling swindlers.” Hubbard had written to the chief of naval personnel, asking permission to sail to South America and China, according to Russell Miller’s Bare-Faced Messiah.

When Crowley told Parsons he was the victim of a con, he flew to Florida. He got a court to put a temporary injunction and restraining order on Hubbard and Betty, preventing them from leaving the country or selling the boats. The couple sailed out anyway.

In a Miami hotel room, Parsons summoned Bartzabel, apowerful demon and the god of Mars. Hubbard’s yacht encountered a storm at sea, forcing them back to port. A court dissolved Allied Enterprises and made Hubbard pay Parsons $2,900.

“Parsons agreed not to press any other charges—partly, it seems, because Betty had threatened to press charges against him over their past relationship, which began when she was under the legal age of consent,” Pendle wrote. “The episode left Parsons shattered. He flew back west. One month later, Betty and Hubbard were married.” They were divorced a few years later, as Hubbard founded Scientology.

But Hubbard succeeded “exactly where Crowley had failed,” Pendle wrote. “He would found a worldwide religion.” In 1969, the Church of Scientology released a statement claiming that Hubbard was “sent in to handle the situation” as a U.S. Navy officer and infiltrate the OTO at 1003 Orange Grove, where he “dispersed” the “very bad… black magic group” and “rescued a girl,” Betty. “Hubbard broke up black magic in America. Hubbard’s mission was successful far beyond anyone’s expectations.”

“There is no doubt that Hubbard’s arrival at the house on Orange Grove signaled a turning point in the fortunes of both Parsons and the OTO, but whether he acted at the behest of a government agency or because of personal motives is a question best left for the reader to decide,” Pendle wrote.

Pendle pointed out the similarities between Crowley’s Thelema and Hubbard’s Scientology, but noted that “while Crowley struggled throughout his life to popularize the OTO, the Church of Scientology became hugely successful. It is, in short, everything Crowley had wanted the OTO to be.”

‘Blown away upon the breath of the fire…’

Parsons sold 1003 Orange Grove and moved into the coach house on the property, and all the weirdos moved out. He soon resigned from the OTO and the Parsonage was torn down to make way for condos.

“The Parsonage had briefly been an adult playground saturated with philosophical hopes and pungent romanticism, fruit brandies and fencing, bohemians and scientists, poetry and rockets,” Pendle wrote. “Now it was gone forever.”

Parsons started attending night classes at USC and looked for a job in rocketry, now an established industry. Shortly after that, the FBI investigated his ties to Communists and the OTO, and his security clearance was revoked and he lost his job at North American Aviation. He and Marjorie moved to Manhattan Beach.

Unable to work in the rocketry field, Parsons turned to his magick and declared himself the Antichrist. His security clearance was reinstated in 1949 and he went to work for Hughes Aircraft, but the FBI soon began investigating him again for suspected espionage, though no charges were filed. (Read part 2 of this series here).

He and Marjorie moved back to Pasadena, just three doors down from the Parsonage, at 1071 ½ S. Orange Grove Ave., a coach house behind the old F.G. Cruikshank estate. He turned the ground floor laundry room into his personal laboratory, where on June 17, 1952, he allegedly dropped a tin can containing fulminate of mercury which exploded and killed him. (Read part 1 of this series here).

Marjorie scattered Parsons’ ashes in the Mojave Desert, where he used to conduct rocket tests.

A few years before his death, Parsons had written to Crowley, “Babalon is incarnate on the earth today awaiting the proper hour of her manifestation. And in that day, my work will be accomplished, and I will be blown away upon the breath of the fire.”

Which, of course, proved prophetic. If nothing else, it can surely be said that Jack Parsons lived fast and died young—and changed humanity’s relationship with the stars forever.