New Film Highlights the Legacy of Local Revolutionary Activist Michael Zinzun

The film, produced by Nancy Buchanan, Derrick Dancer, James Farr and Rochele Jones, features interviews with family members, friends and community members who knew and were inspired by Zinzun, and tells his remarkable life story.

Forward ever, backward never

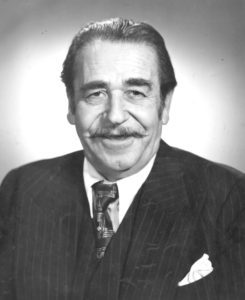

Zinzun was born on Feb. 14, 1949, in Chicago. When his Apache father died when he was eight, his Black mother sent him to live with an aunt in Pasadena. He graduated from Blair High School in 1967 (some reports say 1965) and became a mechanic with a small repair shop in Altadena, until he was evicted by a major oil company.

He joined the Black Panther Party in 1970, which was an educational experience for him, but he left after 18 months because he found it “politically stifling,” he told the Los Angeles Times. He thought the group focused too much on idolizing its iconic leaders and not enough time training up-and-coming activists to rise through the ranks and organize in their communities. So he set out to organize on his own.

“I started to see a guy that was morphing away, and Pasadena was starting to be small,” said classmate Gary Moody, former president of the Pasadena NAACP, in the film. “His likeness was starting to spread. That brother was international. He was way beyond Pasadena. His impact was touching bases all over the world. If it wasn’t for his activism, there would be no Black Lives Matter [movement]. He took it to the nth degree in regards to, not only did it matter, [but] let’s go and do something about our Black lives so we can move forward and have a better life.”

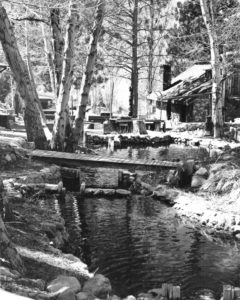

Indeed, Zinzun worked hard to better his community. He supported at-risk youth. He started a free breakfast program to feed kids in Pasadena before they went to school. He launched a free pest control program called “Off the Roach” for poor families who were displaced by the construction of the Foothill (210) Freeway in Northwest Pasadena. The program sprayed over 10,000 houses.

“There were roaches and rats everywhere,” Zinzun told the Pasadena Weekly in 2005. “We were trying to keep them out of the city because they carry disease, and while we were spraying the city government was treating us just like the roaches. They were trying to keep us out.”

Against police brutality

Zinzun was also an early and major figure in the anti-police brutality movement. In 1974, he co-founded Citizens Against Police Abuse (CAPA) along with activists Anthony Thigpenn in Pacoima and B. Kwaku Duren in Long Beach. The organization investigated allegations of police abuse, provided support to victims and families and called for cities across LA County to establish civilian police review boards.

The LAPD swiftly infiltrated the organization and put it under surveillance with J. Edgar Hoover-esque tactics. CAPA and the ACLU sued in 1983, resulting in the disbandment of the LAPD’s Public Disorder Intelligence Division and a $1.8 million settlement.

Shortly after 1 a.m. on June 22, 1986, hearing police arresting a man named Steve Rivers on suspicion of burglary in Pasadena’s Community Arms housing projects, Zinzun and a crowd of 30 people rushed to the scene. They thought the officers were trying to drag Rivers behind a building to beat him, so they called on the officers to stop and show their badge numbers.

Police claimed Zinzun struck an officer, which he adamantly denied. Although he was arrested that night, he was never charged with a crime. As Zinzun was trying to walk away, he was “attacked from behind by five to seven officers who sprayed him with tear gas, placed him in a chokehold, beat him and struck him in the face with a flashlight,” according to the LA Times.

Zinzun suffered a fractured skull and a severed optic nerve in his left eye, resulting in permanent vision loss. He sometimes wore a patch after that, including one monogrammed with his initials. The Police Department released a statement in which they claimed that the damage to Zinzun’s eye occurred when he fell onto the sidewalk during the scuffle.

“Michael was responding to a situation in the community where the police were just going hands off, very heavy handed, and using excessive force,” Farr said in the film.

Prosecutors declined to charge the two officers involved, Jim Ballestero and Chris Vicino, so Zinzun sued the city of Pasadena, which awarded him a $1.2 million settlement.

“I’m more determined than ever,” Zinzun told a Times reporter a month after the incident. “I’ve got my designer patch. I’d rather lose an eye fighting against injustice than live as a quiet slave. I just can’t see myself standing back. I will continue what I am doing. I am not going to stop.”

He established the Michael Zinzun Defense Committee to help defend others who experienced police abuse.

“Many people think that my father hated the police, but that’s such a big misunderstanding,” Michael Zinzun Jr. told Pasadena Black Pages. “He didn’t hate the police, he hated the abuse of authority. The slave-master mentality that the police force attracted.”

Vote Zinzun

Also in 1986, Zinzun ran for California state Assembly in the 55th District on the Peace and Freedom Party ticket. He polled higher than 10 percent in the primary that year, but Democrat Richard Polanco went on to win in the general election. Zinzun’s platform included “jobs with peace, affordable housing (immediate rent freeze), diverting military money to jobs, divesting California from [apartheid] South Africa, stopping the death penalty, bilingual education and no prisons in the 55th District.” Politically, he called himself a “radical Socialist.”

In 1989, Zinzun ran for a third time for a seat on the Pasadena City Council, then called the City Board of Directors.

During that campaign, LAPD Assistant Police Chief Robert Vernon, a Christian fundamentalist who lived in Pasadena’s Linda Vista neighborhood near the Rose Bowl, took files from the LAPD’s Anti-Terrorism Division and leaked them to the press, which gave the public the false impression that Zinzun was under investigation for terrorism. Zinzun sued Vernon and the city of Los Angeles for defamation and a jury awarded him $3.8 million from the city and $10,000 from Vernon personally. In 1991, that ruling was overturned on procedural grounds. On appeal, Zinzun was ultimately awarded $512,500.

Vernon argued at the trial that he only used the LAPD’s computer to obtain newspaper articles about Zinzun which he then gave to his neighbor, former Pasadena Mayor John Crowley. Either way, the damage was done when the Anti-Terrorism Division became known as the source.

Zinzun said the settlement didn’t “make up for the fact that they chose to violate my civil rights. Right in the middle of my campaign, I was labeled a terrorist. This may have hurt me in one way, but in some [other] ways I do believe [it resulted in] the community becoming more and more aware of how the police can manipulate or attempt to manipulate public opinion.”

Also during the Pasadena campaign, Councilman Bill Paparian endorsed Zinzun over Chris Holden, son of then-LA City Councilman Nate Holden, who would go on to become a state Senator. Chris Holden ultimately won the Pasadena race, went on to become mayor of Pasadena when it was a rotating position on the council and has served in the Assembly since 2012. Zinzun was just 48 votes short of a runoff in that 1989 election.

“The late Loretta Glickman, the first African American mayor of Pasadena, was retiring, and Michael [Zinzun] announced his candidacy,” Paparian said. “I announced I was going to support Michael. I knew of him, I knew of his work regarding police misconduct and police reform. I knew of his involvement in the lawsuit that had been filed against the intelligence division of the LAPD that resulted in a settlement. I knew of his history with the Black Panther Party, and I knew of his work in Northwest Pasadena. He was an important person in the community.”

After the election, Paparian nominated Zinzun to Pasadena’s Northwest Commission in 1990, but the other members of the City Council refused to support his appointment.

“What is it about someone having been associated — in Michael’s case, for a brief period of time in the 70s — with the Black Panther Party that would be cause for them not to be considered for appointment to an advisory post for the city of Pasadena, when it’s someone who was currently active in the community, who was doing all kind of things for the community in a positive way?” Paparian said in the film.

In 1999, Zinzun, Paparian, Holden and several others ran for mayor of Pasadena, according to the Weekly, a race ultimately won by Bill Bogaard. Holden appointed Zinzun to the Pasadena Community Access Corporation’s (PCAC) Board of Directors in 2000.

‘Message to the Grassroots’

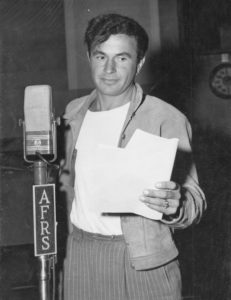

In the early 1990s, Zinzun launched his own hour-long, monthly TV talk show called “Message to the Grassroots,” which he hosted for nearly 10 years and co-produced with artist and activist Nancy Buchanan, who also produced the film. The show aired on Pasadena Media, the local public access channel, then called KPAS on Channel 56.

“Michael was a big proponent of cable access and fought hard to bring it to Pasadena,” Buchanan said in the film. “If there was going to be cable, [Zinzun lobbied] to have public access be required. He always understood how important media was.”

Farr said the film’s producers pored through more than 100 hours of Zinzun’s show. In one episode, Zinzun organized one of the first ever face-to-face truce meetings between members of the warring Bloods and Crips in the same studio. He was a major proponent of a truce between the rival gangs. In another episode, he provided analysis of the video of the beating of Altadena resident Rodney King by four LAPD officers, and talked to John Burton, a Pasadena lawyer specializing in police misconduct cases, just days before the LA Riots in April 1992. Zinzun also debuted footage of the beating from a second camera.

Zinzun served as the grand marshal of Pasadena’s Black History Parade twice, the only person to do so. And his activism extended beyond Southern California as well. He called for California to divest from South Africa during apartheid, spoke out on behalf of Namibians fighting for freedom and called attention to human rights abuses in Haiti. His most lasting legacy, however, remains his impact on the movement for civilian oversight of the police, a dream partly realized with the establishment of Pasadena’s Civilian Police Oversight Commission last year.

Haywood released another film last year about tensions between Pasadena police and Pasadena’s African American community called “Thorns on the Rose: Black Abuse, Corruption & the Pasadena Police,” which was also produced by Farr and Jones. Funds raised from donations and proceeds from that film were awarded to local student Noah Griffin of Muir High School as part of the Anthony McClain Social Justice Scholarship.

‘An extraordinary force for justice’

In his later years, Zinzun was planning to become a chef. He had enrolled in a course at Pasadena’s Le Cordon Bleu culinary school. He passed away in his sleep on July 6, 2006, at age 57. He and his wife Florence, prominently featured in the film, had six children and 19 grandchildren, in addition to a seventh child he had with his first wife in 1968, Zinzun Jr.

“He was just an extraordinary force for justice and the civil rights movements,” Barry Gordon, who served on the PCAC board with Zinzun, told the Weekly. “He matched his passions with the principles.”

“Zinzun: A Revolutionary Activist” may be rented or purchased for limitless views at https://vimeo.com/ondemand/zinzun/677444909